AR Shaw Books - Limited Time Offer

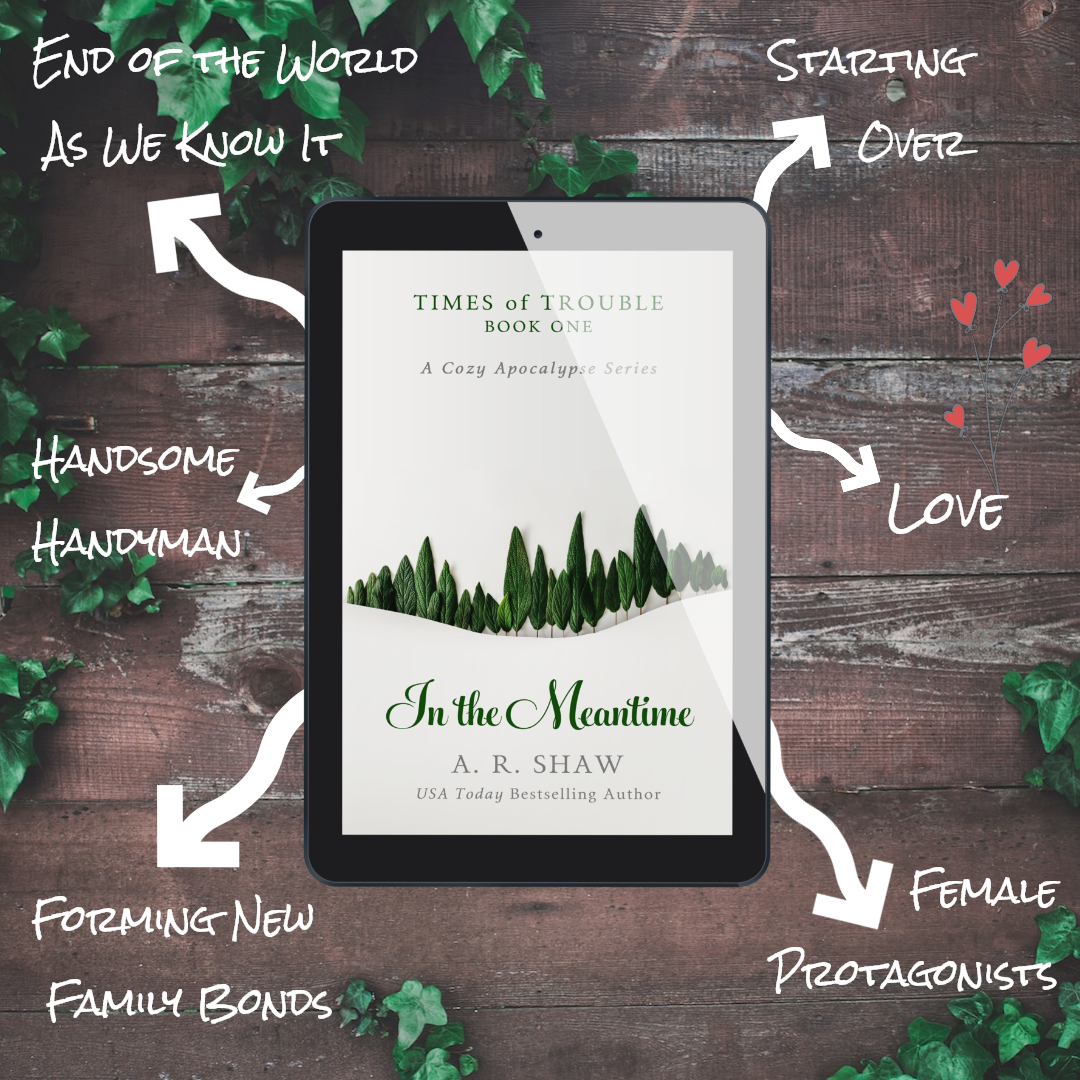

The Best Cozy Apocalypse Bundle

The Best Cozy Apocalypse Bundle

Couldn't load pickup availability

📕 E-Book Bundle

🔵 Get Instant Gratification

- Purchase the eBook instantly

- Receive download link immediately via email

- Send to preferred ereader and enjoy!

🔵 Click Below to Explore Your Stories:

Times of Trouble Series: Discover how two ladies in the small town of Silverdale, Washington serve justice after the collapse 🚜☕️🌻

Times of Trouble Series: Discover how two ladies in the small town of Silverdale, Washington serve justice after the collapse 🚜☕️🌻

“Andrew!” Hilda Jo tossed her red curls over her shoulder. She must’ve been freezing, Irene thought, not that anyone would notice with the amount of makeup she was wearing.

“Just the man.”

Andrew settled the armful of jars that he was carrying into the back of the pickup and went over to the fence. “Hilda Jo,” he said. “How can I help you?”

“It’s my bed.”

Irene almost dropped what she was carrying but quickly covered up her snort by pretending to trip over a rock on the driveway.

“Your bed?” Andrew asked innocently.

“It’s developed a squeak and it’s keeping me awake at night. I wonder if something needs tightening.”

Irene rolled her eyes. Straightening, she glanced at them standing either side of the fence, Hilda Jo twisting the string of pearls she was wearing around her fingers. Any moment now, Irene thought, she’s going to wrap that string around his neck and drag him into her lair, and he’ll never be seen again. She mentally shook herself at the vivid images in her head. Maybe she should stop reading fantasy for a while and pick up some cozy mysteries next time she visited the library.

“I’ll pop in next time I’m passing by,” Andrew said.

He went to walk back to Irene, as the other woman caught his hand and said, “Do you not have time right now? I left the bed unmade just in case...”

🔴 Read Chapter 1 - In the Meantime

🔴 Read Chapter 1 - In the Meantime

Irene lowered the back of the pickup truck and caught one of the smaller pumpkins as it tried to roll over the edge. The whole load shifted slightly, as if the escapee had triggered a domino effect amongst the cargo of ripe, fleshy fruit, and, despite her petite frame, Irene spread her arms like a scarecrow ready to catch any others that threatened to fall.

“Will you be making your pumpkin pie again?” Sylvia asked. The younger woman hung back, rubbing her hands together and blowing into them to keep them warm.

“It wouldn’t be a feast without it.” When she was certain the load was stable, Irene gestured to Sylvia to help her start unloading the pumpkins into the barn. “We’ll can and pickle the rest to see us through the winter.”

Irene was unsure how it had happened—it had been a gradual evolution, she supposed, a role she’d gravitated towards as one of the older members of the community—but she secretly liked it when the younger folks looked to her for guidance or expected her to provide all the answers.

When she was younger, if anyone had suggested that this might be where she ended up, in her hometown of Silverdale, Washington, harvesting fruit for the winter and discussing her famous pumpkin pie with the end-of-fall feast in mind, she’d have dismissed it without a second thought. Irene learned all her traditional skills from her grandma, who maybe envisaged more than she ever let on. Baking. Sewing. Knitting. Young Irene had the patience to learn such hobbies, because while she was sitting quietly with Grandma inside the cozy house, she didn’t have to worry about friendship groups that she was always too intimidated to wriggle her way into. Jigsaw puzzles: another pastime high on the older woman’s list of favorites. She loved to read too, and it scared the life out of her to think that once she exhausted the supply of books in the local library, she’d never again experience the joy of reading the first page of a new story.

Sylvia glanced at the Olympic Mountains with their snowy hats in the distance and shivered as she reached for one of the larger pumpkins. “There’s a bite in the air already,” she said, eyes lowered. “I don’t remember it being this cold this early last fall.”

“Well, I recall adding a little extra spice to the soup when I prepared the first batch.” Maybe this was why Irene was a natural matriarch—she didn’t pander to the whims and worries of the youngsters. “Whatever comes our way, we’ll deal with it together, same as we always do.”

She nudged open the barn door with the heel of her boot and inhaled deeply as she stepped inside. Irene loved it when the barn was filled with the food they’d cultivated during the summer. Even if she closed her eyes, the smell of earthy potatoes, bulbous rutabagas, crunchy carrots, and parsnips, and all the other vegetables and fruit they’d already stored in here ready for winter preparations, filled her with warmth and satisfaction. She’d felt the same way when her son David was a little boy and she watched him devour his favorite meal. Providing food for others was the most gratifying feeling ever.

“I remember mild winters from when I was a little girl. It confused the animals that were supposed to be hibernating, so they didn’t know whether to cozy up or stay awake. Nature has its seasons for a reason.” Irene lowered the pumpkins gently onto the barn floor beside a heap of fat sweet potatoes. “Why do you think all this food harvested in the summer is perfect for winter fare?”

“I guess.” Sylvia shrugged. “I look forward to winter food more. Pies. Soups. Broths.”

Irene straightened and smiled. “That’s just your body’s way of dealing with the lower temperatures. Comfort food. There’ll be plenty of that with this lot.”

They stepped back outside to collect more pumpkins from the truck. The truck’s paintwork was starting to rust in places she noticed, the red over the wheel arches corroding and turning mottled, fiery orange and dank green. Winter colors.

It was peaceful. The sky was solid blue like a child’s painting, the fir trees tall and majestic, the water smooth as glass. Irene loved the peace, wore it around her shoulders like a fur-lined cloak, buried her head in it sometimes. Like now. She hadn’t been entirely honest with Sylvia. The winters were harsher now, last winter the coldest so far, and she sensed the chill in the air too. But it was all about perspective. They had a barn full of food—well they would have once they finished unloading the pumpkins—a couple of the men were out there now chopping logs for firewood, the whump-whump of their axes as comforting as the peace they were disturbing, so they’d have warmth too. What more could they possibly want?

Sylvia’s face was turned toward the sky. Her nose was pink. She wore a sweater beneath a flannel shirt, but Irene noticed the way her collarbones protruded above the neckline of the sweater, the way her bony fingers twitched in the cold. She couldn’t help herself. She felt responsible for keeping the younger members of the community happy. She still had wool. When she was done preparing food for the end-of-fall feast, she would start knitting a scarf for Sylvia and maybe some mittens. Her patterns were so old that she could barely read the words on some of the pages, or maybe that was because she needed new prescription spectacles, and she’d felt the first twinges of arthritis in her swollen thumbs last winter, but she’d take her time. She might even ask her next-door neighbor Hilda Jo if she could tease a few strands of glitter from some of the cocktail dresses she still clung to in the hopes that, one day, she’d be invited to another party where she could out-sparkle the other guests. Sylvia would appreciate that, she hoped anyway.

They worked up a sweat shifting the cargo from the back of the truck, Irene secretly squeezing the fattest pumpkins and setting some aside to make pie.

“I remember carving faces out of pumpkins when I was a little girl,” Sylvia said. “Mom would put tealight candles inside and we’d place them all around the house. The scarier the faces, the better. We’d give them fangs and bat wings and everything.” The younger woman’s face lit up with the memories. “I remember she made special spooky suppers. She made me put my hand on a slice of bread so she could cut around it, and then she’d chop off the ends of the bread fingers and trail ketchup from them like blood.”

Irene laughed. “I remember adding red food coloring to soup and floating plastic eyeballs in the bowls to scare David. One time, he must’ve been around six or seven, he dressed up as a zombie to go trick-or-treating, and he refused to take that costume off for a week after.”

Did that make her son sound precocious? She hoped not. At the time, she’d battled with him to get the tattered costume off and get him into some decent, clean clothes for school, but her memories were rose-tinted now, and all she could see was his chubby face and his perfect smile and how she’d pretended to be scared when he gave her his best zombie impression.

Sylvia picked up on the older woman’s reminiscing. “My mom dressed me up like Wednesday Addams one time,” she said. “Bought a black wig with long black pigtails and dressed me all in black, then she made me promise not to speak or smile or react to anything. I just had to stand dead straight when I knocked on folks’ doors and stare them out until they got spooked and handed over some candy.”

Irene faced her, adding a tiny pumpkin to the pile in the other woman’s arms. “Did it work?”

“I think so. I remember my mom laughing all the way around town and telling me that I was destined for the stage.” Sylvia waited for Irene to gather a pile of pumpkins into the pouch that she’d made from her jacket, before heading back inside the barn.

Maybe that’s what they were missing, Irene thought. Why couldn’t they combine the feast with a Halloween celebration? They could spare some of the smallest pumpkins for decorations, and she was certain Hilda Jo would want to jump on the bandwagon and provide the costumes and makeup if it gave her a chance to shine. Sure, things had changed, but it didn’t mean they had to give up on whatever made them happy. Life was still for living, right? Or else, what was the point?

She didn’t say anything to Sylvia in case the others dismissed the idea without a debate, but she could picture it already, the feast alive with flickering candlelight, the table heavy with hot food, and flowers, and even some of the mayor’s wine. She might even carve hand shapes from toasted bread, like Sylvia said her mom used to do, just to put a smile on the young woman’s face.

Smiling to herself, she finished unloading the truck.

🔴 Read Chapter 2 - In the Meantime

🔴 Read Chapter 2 - In the Meantime

With the truck emptied, the two women set about chopping up the pumpkins. Irene had brought a large basket from home, and it soon began to fill with large chunks of juicy flesh. Setting the seeds aside for replanting, they discarded the stringy parts of the flesh to leave out for the wild animals to feast on. Irene was a firm believer in making everything count, and the creatures were only trying to survive too, so why shouldn’t they get their own end-of-fall feast? She’d already prepared the jars for canning. They sat in a row on her kitchen counter, spanking clean, and waiting to be filled.

She loved the sight of jars filled with preserved food. Was it human nature? The world was filled with all these wonderful fruits and vegetables, in glorious reds and oranges and yellows and mauves, and the hours she spent filling the glass containers with food that she knew would see them through the winter were some of her happiest. She felt like a squirrel admiring a stash of nuts, knowing that she’d still be happily full when the world outside turned white.

Sylvia, she noticed, was a little squeamish when it came to chopping the fruit, flicking the seeds from her jeans, and picking the stringy flesh up between thumb and forefinger like it was something toxic.

“Get stuck in,” Irene said. She gave the younger woman a demonstration in how to get the best of the firm flesh. “Don’t be afraid of it. It won’t bite.”

The barn gradually filled with the sweet pumpkin aroma. One thing she had to say for nature, it always came through when humans needed it most.

“Careful!” A voice reached them from the barn entrance. “Almost got me.” The woman pulled a pumpkin seed from the red bangs framing her immaculately made-up face.

“Sorry.” Sylvia smiled up at the new arrival and immediately set about picking stringy orange flesh from her clothes and rubbing away the damp patches.

Hilda Jo had that effect on people. Even now, after everything, Irene had never seen the woman leave the house without lipstick and mascara, and who knew how she kept her hair that precise shade of red-with-a-hint-of-gold. She liked to imagine her neighbor brewing a red potion in the dead of night, a veil of cloying, devilish mist floating around a heavy, black cauldron … but maybe she was doing Hilda Jo a disservice. Maybe she was a natural redhead as she claimed to be.

“You could always help instead of standing there making the place look untidy,” Irene said. She brought the cleaver down heavily on a chunk of pumpkin and took pleasure in making the other woman jump.

“I’m looking for George,” Hilda Jo said.

Irene peered around the barn and lifted the largest pumpkin that remained to be cut up, gazing at the empty space underneath. “Nope. Not seen him anywhere.”

Hilda Jo rewarded her with a dazzling smile. Irene bet she’d been perfecting it in front of a mirror since she was old enough to talk. She could imagine the other woman as a child, stamping her dainty foot and demanding attention. Irene was born and bred in Silverdale, but Hilda Jo was raised on a farm in Kentucky, the only daughter of a horse breeder and an actress. She claimed to have six older brothers who taught her how to knock out a man with one punch by the time she was thirteen and milk a snake so that she could suck the poison from a deadly bite and cure it in the blink of an eye.

Irene didn’t believe the stories no more than she believed the hair color was natural, but others seemed to cling to Hilda Jo’s every word. Even now, Sylvia had abandoned the slimy knife she was holding and was watching the other woman, wide-eyed, taking in the clean, ivory pants, and the tasseled jacket that resembled an outfit from a glitzy, Vegas cabaret show.

“Very funny,” Hilda Jo said. “My, what is that smell?”

Irene instinctively tilted her face and sniffed. “What?” she said. “What is it?”

Hilda Jo wrinkled her nose, taking care not to reveal too much of her nostrils, and said, “Oh, silly me, it’s the pumpkins. I’ve never gotten used to that sickly stench. It’s quite overpowering, isn’t it? It’s a wonder you two can breathe in here.” She turned away so that she was facing the outside, leaned against the doorframe, and made an exaggerated gesture of sucking in great gulps of air.

Irene rolled her eyes. Always the actress; it was a wonder everyone still fell for it.

Sylvia laughed, her features coming alive. “What will you be making for the end-of-fall feast?” she asked.

“I’ll be making my sweet potato pie as usual.” The redhead’s smile was back. “You can’t beat ‘em. Everyone said so last year.”

“Everyone?” Irene’s eyes narrowed.

That wasn’t how she remembered it from last fall. Same as it wasn’t how she remembered it all through the winter either; everyone loved Irene’s pumpkin soups. And her pickled squash chutneys. The pear chutney always went as a treat over the holiday season, but she’d deliberately saved the new recipe, the squash and plum chutney, for the Christmas meal the community came together for. She recalled the praise she’d received as they stuffed themselves on George’s mature cheese and Irene’s squash chutney along with Hilda Jo’s spicy biscuits. “Crisped to perfection,” was the comment most bandied about. She’d had several glasses of wine by this point, but she was almost a hundred percent certain they’d been talking about the chutney and not the biscuits.

“I think the cleared plates were the giveaway.” Hilda Jo examined her fingernails which were perfectly coordinated with her hair and lips as though she were headed for a night on the town and was waiting for a stretch limo to pull up outside.

Irene shook her head. She shouldn’t bite; she promised herself each morning when she opened her curtains and saw Hilda Jo’s curtains still closed, that she wouldn’t bite again, that she’d allow the woman’s words to wash right over her and act like she hadn’t even heard them. Then Hilda Jo opened her mouth and somehow, she couldn’t stop herself being sucked right in. “The pumpkin pie plates were all cleared too.”

“The birds have to eat something, poor little dears.”

“I love both pies,” Sylvia said, her gaze flitting between the two older women. “I’ll take a slice of both with cream and brown sugar. Dad will too.”

“You’re a honey.” Hilda Jo blew her a kiss. “Maybe we should set ourselves a little competition. See whose pies get eaten the fastest.” She arched her perfectly tweezered eyebrows. “What do you say, Irene?”

“Bring it on.” Irene had heard the phrase used by the Perez kids; she wasn’t entirely sure if it was appropriate right now, but it seemed to fit the purpose, and the words were out before she could stop herself.

Sylvia chewed her bottom lip. “Will there be a prize for the winner?”

“Oh, I’m sure we’ll think of something,” Hilda Jo said.

“Perhaps I can make a crown for the winner.” Irene was thinking of a whimsical ring made from dried grasses and twigs, pretty daisies and tiny, blue cornflowers woven amongst them. The headdress conjured up childhood images of fairies and sprites, toadstools and wishing wells, and the magical cupboard that led the Pevensey children to Narnia.

“I have just the thing.” Hilda Jo smiled at them. She’d still not set foot inside the barn as if the pumpkin scent had created an invisible barrier preventing her from coming any closer. “It’s the cutest tiara once worn by Grace Kelly in an old 50s movie.”

Irene puffed up her cheeks and then, when she realized that Sylvia was watching her, tried to smooth the action into a smile. “How do you know it was worn by Grace Kelly?”

“My ma bought it from a vintage shop. It came with a written guarantee.”

“So do a lot of things,” Irene mumbled.

“It sounds awesome.” Sylvia was still wide-eyed.

“You’ll be helping me make the pies?” Irene asked her now.

If it meant the younger woman got to feel like Grace Kelly for a night, she supposed it would be worth allowing Hilda Jo her moment to gloat over the tiara. Come to think of it, Irene wasn’t even convinced that Hilda Jo made her own sweet potato pies. She claimed the recipe had been handed down to her by her grandma, but the woman claimed a whole lot of things that were equally as unbelievable; what did she do with all those rings and bracelets while she was elbow-deep in flour?

“Sure,” Sylvia said, sounding even less sure than she’d been when they first arrived at the barn. “I was going to ask if you’d teach me how to make corn husk dolls for the table too.”

Irene’s shoulders relaxed a little, and she smiled at the young sandy-haired woman. If her fingers weren’t covered in pumpkin pulp, she’d have hugged her right about now. “It would be my pleasure.”

Hilda Jo eyed up the basket and the remaining pumpkins scattered around the two women. “Here’s an idea,” she said. “Why don’t we combine the end-of-fall feast with a Halloween celebration? We could carve pumpkins—if you can spare some of course—and, Sylvia, you could help me make some lanterns to string around the picnic area. We could all dress up in costumes. I have the most authentic witch’s cloak you ever did see in a trunk in my attic. I once played a sexy witch in a stage production of—”

“I was going to suggest a Halloween celebration myself,” Irene interjected.

“Well, then, I’m glad I beat you to it. It’ll be so much fun.” Hilda Jo was still grinning as she left the two women in the barn and went to retrieve the promised costume from her attic.

🔴 Read Chapter 3 - In the Meantime

🔴 Read Chapter 3 - In the Meantime

At home, Irene was in her kitchen preparing the pumpkin for the pies. She’d been replaying in her head, the conversation between her and Hilda Jo that occurred in the barn, still trying to figure out how the woman had manipulated yet another situation to make it seem that she was the creative one. Had she overheard Irene and Sylvia discussing Halloween? No, she couldn’t have because they were still carrying the pumpkins into the barn at that point, and there was no way Hilda Jo would’ve kept quiet for so long before she felt the need to interrupt them. She must’ve noticed that Irene had set some of the smaller fruits aside for Halloween decorations. That was it. Irene only had herself to blame for not speaking up sooner. It was the story of her life.

She opened the cabinet above her head and located a small glass jar, right at the back of the shelf. It was her secret ingredient. Cardamom. Unlike her neighbor’s fanciful stories about family recipes and tiaras worn by real-life princesses, this trick had been handed down to Irene by her mother-in-law. It would’ve worked a whole lot better if she could get hold of some fresh vanilla pods, but there was nothing she could do about that. Her only consolation was that, if she couldn’t get vanilla, neither could Hilda Jo.

Irene’s husband Bill used to love her pumpkin pie. Maybe that’s why the recipe was so precious to her. She smiled to herself and inhaled the spicy aroma with the freshly added ingredient. Her husband would come home from work, walk into the kitchen, and close his eyes in anticipation when he realized that his wife had been baking. She closed her own eyes, remembering.

They say that if you want to sell a house as a home to a prospective buyer, you should have coffee brewing and a pie baking in the oven when they arrive to look around. There had to be some truth in that, she thought. Even though she’d not yet put the pies in the oven, she could already smell the sweet aroma and was instantly transported back to when her son David was a growing lad.

He was into his sports and athletics. He never stopped moving. Fidgeting, climbing, running, spinning around. When he was at kindergarten, Irene had worried that he might have an underlying condition, ADHD, or something similar; not that she wanted to put a label on it, but he simply found it impossible to keep still and his attention rarely lasted longer than a few minutes unless he was performing a physical activity. She’d gotten him into every sports club that she could afford to send him to, and he excelled at everything.

She remembered how proud of himself he’d been when he won his first medal in gymnastics. “I’m going to compete in the Olympics when I’m older,” he’d said, his beautiful face already smiling at the image of him standing on a podium, receiving his gold medal.

Tears welled in her eyes, and she sniffed loudly, dabbing her face with the hem of her apron. He was eleven when he was hit by a car. Too young. His left leg was shattered, and they’d had to pin it back together again with metal plates and steel pins. He always joked that his leg set off the alarms in the airport whenever he traveled; he even carried his medical records around with him to prove that he wasn’t trying to smuggle an illegal item onto the flight. It didn’t stop him though. He transferred his passion to sailing.

Irene slid open the second drawer of the cabinet beneath the floury counter and pulled out a picture of David standing beside the two-person sailing dinghy he was traveling in when the apocalypse hit them. He was with Gabe, his best friend from middle school who’d remained his closest friend all through high school, and college, and beyond. They were traveling around the Bahamas.

She traced her son’s face with her fingertip. She’d not even worried when he announced their plans for the summer. He’d been sailing competitively for around ten years at that point, since he was fourteen, and he’d traveled further than the Bahamas on his own, so when he told her that Gabe was going with him, she imagined a summer of island-hopping, one spectacular panorama to another. Beach parties spent chasing the sunsets. Snorkeling. Scuba diving. Swimming with sharks. She’d kissed them both goodbye without ever knowing that would be the last time she’d see them.

Would she have acted differently if she’d known?

If someone had said to her “Irene, you’ll never see David again, so what do you want to say to him?” would she have begged him not to go?

She didn’t think so. But David was the reason why she’d never left Silverdale. What if he came back tomorrow and discovered she was gone? He’d have no way of tracing her, and she’d never be able to live with that. She had to live in hope—what else did they have?

Sometimes, she saw the way some of the others watched her, especially when they came together as a community and reminisced about the days before everything changed. She didn’t need anyone to spell it out. She knew the chances of David returning were slim, but they were not zero. Even if they were, she’d still be here, she thought, but her neighbors didn’t need to know that.

The spores that killed most of the world’s population circulated around the planet from the ocean. She wasn’t in denial. She’d avidly followed the news her entire life, taken an interest in politics, in world affairs, in climate change. So, when ecologists announced that they’d developed a fungus to clean up the oceans of oil spillages and the tons of plastic that was killing marine life, she’d spent hours poring over articles baring the pros and cons of the procedure. Scientists declared that it was harmless to marine life and humans. Not entirely without risk, but was anything? They’d tested the fungus. The results were nothing short of miraculous, although they were vague about the figures, the different media outlets providing conflicting information aimed to confuse the general public. Until the miracle became something else. The new miracle, one that the scientists hadn’t predicted was that, out of a population of almost 350 million, only a couple of thousand people possessed a natural immunity to the spores that drifted inland from the ocean. Everyone else died from the subsequent respiratory infections. Her husband Bill was a casualty of the apocalypse. Same as Hilda Jo’s third husband Dirk.

Yet Irene and her neighbor were both immune. They had no way of discovering what made them any different to the people who died, but Irene clung desperately to the hope that whatever she had was genetic and that she’d passed it onto David. He had his dad’s eyes, that was undeniable, but he’d inherited every other feature from his mom. Each morning, before she climbed out of bed, Irene kissed the framed photograph of David that sat on her bedside table and prayed that he’d inherited her immunity. “Please, God,” she whispered, “if I gave him anything, please let it be that.”

Most people had migrated away from the coastal areas, hoping to avoid the toxic spores inland. But Irene stayed. Hilda Jo stayed because she refused to leave her horses behind; the woman had a heart buried somewhere beneath the glitzy sweaters and the delusions of grandeur. The others stayed because … well, Irene guessed they all had their reasons. Some she could guess at; others were less obvious. Nonetheless, they’d all come together as a community in a way they never had before the end of the world as they knew it.

Irene had read many dystopian books in her time, all predicting that, in the event of a catastrophic, global pandemic, humans would turn against one another in a final struggle for power. As if trying to survive would not be difficult enough. But in Silverdale, they’d gravitated together, joined forces to see this thing through, drawing on each other’s strengths and skills, and learning to get along with one another. It was all about gratitude. They were grateful to still be alive. Grateful for what they had. Some, more than others maybe, but she could ignore petty squabbles when she thought about her son.

There was no one to man the power stations when the apocalypse wiped out the nation’s population, so they’d reverted to the old ways of cooking over wood-burning stoves and powering their homes with individual solar generators. Their cell phones had still worked until they’d not been able to charge the batteries.

So, she had no choice but to stay here and wait for David. Even if she was the last woman standing, she’d still walk down to the marina each evening before sunset and scan the horizon for a glimpse of a sailboat before whispering to the moon to bring him home safely.

Disasters in a Jar Series: Discover individual stories of disaster and recovery ☄️🌊🏚️

Disasters in a Jar Series: Discover individual stories of disaster and recovery ☄️🌊🏚️

Disasters in a Jar Series: Individual Stories of Hope when Mother Nature, Murphy, or Mankind has other ideas.

John Hollie:

"I was devastated when the Wash Out hit. I had just purchased my dream house in a prestigious community, but I lost everything in a matter of days. The flooding was rampant, and the ocean had taken over the land. But it was a man-made disaster that left the world in ruins. And you'll never guess who the culprit is..."

🔴 Read Chapter 1 - John's New Place

🔴 Read Chapter 1 - John's New Place

“Okay, so I want to show the viewers again how the Earth works.” A diagram zoomed onto a black background and enlarged itself to cover the entire surface. It was simple and covered the four layers of the Earth’s crust.

A man’s voice spoke over the image. “The tectonic plates, when viewed together like this, form the lithosphere. They’re sixty-two miles thick, but are made up of two different crusts, as opposed to one solid crust as you might imagine. We have the continental crust and the oceanic crust. Two extremely different densities which is why they are sometimes caused to shift and which, in turn, causes friction between the plates.” The image on the screen panned back to the expert currently being interviewed by the reporter: a man in a scruffy gray suit, his hair tousled like he’d been dragged straight out of bed and into the studio. He aimed his hands at the camera, side-by-side, lowered his right hand a fraction and then made a sawing motion with them to demonstrate the movement.

“So, this friction,” the news reader said, “is what’s called subduction?”

“Correct, Penny. Energy accumulates between the plates as they shift. Imagine a spring—what were those toys called that we used to play with when we were kids?”

The camera caught the spontaneous frown on Penny’s face, instantly replaced by the usual smile, and wide, innocent eyes. “Slinkies?”

“Slinkies, yes,” the expert continued, oblivious to the young woman’s reaction.

John Hollie, watching the news report on his cellphone, smiled to himself as he stirred scrambled eggs in the tin pot on his camping stove. Studio dynamics generally intrigued him more than the report itself—he often wished he’d gone on to study psychology in college—but today’s interview was of particular interest to him, given the events of the past twenty-four hours.

The man pressed his hands firmly together. “Imagine a compressed spring. What happens when I remove my top hand?”

“It springs up?” Penny said.

“Exactly. It springs back into position. Now, when this happens in the ocean, the force of the movement creates a huge wave.”

“A tsunami.”

“A tsunami, correct. These waves can travel long distances. Generally, what happens before a tsunami hits land is that the shallower water slows the wave causing the height to increase. Scientists call this the trough. Water retreating from land is often a sign that a tsunami is approaching.”

Another diagram of the so-called ‘Ring of Fire’ appeared on the screen, the area off the coasts of Chile, Japan, and Indonesia, where earthquakes and tsunamis are most common. This was followed by video footage of a tsunami hitting a coastline.

Hollie stopped stirring his eggs and watched, open-mouthed. The height of the wave, when you realized that this thing was real and not just a scene from a movie, was terrifying. Imagine that coming at you, he thought. You wouldn’t stand a chance. The footage immediately switched to scenes of mass destruction: buildings flattened, entire coastal resorts underwater, trees and debris being carried along on a torrent of dirty water.

“There are three main forces behind the movement of the tectonic plates,” the expert continued.

Penny glanced at the camera and fidgeted in her seat.

“Let him speak,” Hollie said out loud, realizing that she was trying to hurry the scientist up and bring the interview to a close. “You got him in there for a reason.”

“Basically, it’s all down to gravity.”

Hollie sighed. He was expecting more.

“We all know that heat rises. The newly formed oceanic plates are warm, while the older plates are cooler, which makes them denser, which in turn causes them to sink, dragging the warmer plates down with them.”

“So, this is a natural occurrence is what you’re saying?” Penny asked.

“Climatologists have been warning us about this for years. Decades. We’ve been repeatedly warned that if we didn’t make serious attempts to reverse the damage already caused to the ozone layer, this would happen.” The man’s voice was rising, his words tumbling out as if he realized that the interview was being cut short. “Now, what we’re seeing is a direct result of—”

Hollie’s screen went blank.

He grabbed the phone from his foldaway camping chair and pressed the ON button. His battery must’ve died. A burning smell behind him caused him to drop the phone back onto the canvas seat where it promptly slid off and hit the grass underneath. His eggs were burnt. Hollie removed the pot from the low flame and stirred the lumpy mixture, black flakes getting caught up in the top layer, the part he should’ve been able to salvage. Oh well.

He sat down and ate breakfast straight out of the pan, blowing each spoonful first. Yesterday, he’d jumped in his boat and set off with no destination in mind; he simply wanted time to think, and the boat always helped. It was the reason he’d moved to his new home by Lake Erie in the first place—that, and the project that the universe had sent his way at the right time. He loved being close to the water. It was therapeutic. Relaxing. Some people had dogs—Hollie had his boat.

He’d tuned into the news report because he hoped it might shed some light on what was going on right now. The night before, he’d found a secluded area to moor the boat, read fifty pages of a thriller novel written by his favorite author in bed, his eyelids drooping with the gentle lap of water against the side of the boat, and slept on it, certain that an explanation would’ve at least begun to form in his mind. But he was still bewildered. The scientist hadn’t told him anything that he didn’t already know either.

Hollie’s seat gave him a perfect view of the lake and not a single soul staring back at him. Since relocating here, he’d realized that, in the city, with the relentless noise and traffic and long days spent at work, he’d never truly relaxed. He’d always been in fight or flight mode, shoulders tensed, eyes narrowed. Here, he felt the tension physically draining from him at the end of the day over a cold beer and a plate of nachos. Here, he didn’t have permanent grooves between his eyebrows.

He hadn’t been out to the islands yet. Maybe in the summer. He closed his eyes, soaking up the sun’s gentle rays, feeling the warmth seeping through his skin. How did some people spend their entire lives in the city? They never got to experience peace of this magnitude, the water rippling onto the shore, the fish nipping to the surface, the birds singing.

His eyes flew open. The birds had stopped singing. His Spidey senses were switched on, the hairs on the back of his neck standing up, the blood gushing in his ears.

Then he saw it. The huge wave hitting the land east of where he was sitting, like this were nothing more than a sandcastle being flattened beneath a child’s bucket of water. The pan hit the floor, specks of scrambled egg mingling with the grass. Hollie stood, the camping seat tumbling backward.

He froze. If he’d not just watched the news report about tsunamis and tectonic plates, he’d have squeezed his eyes shut and told himself that he was dreaming. Tsunamis didn’t happen here. He mentally shook himself. Even if tsunamis did happen here, they hit the coast, they didn’t travel inland before they came crashing down. His breath caught in his throat. If this was a tsunami…

Hollie covered the few steps between him and his boat in an instant, his feet barely touching the ground. The moment his feet touched the deck, he whipped the penknife from his pants pocket and began carving through the mooring rope; he didn’t have time to loosen the knot, and besides, his hands were shaking so badly, his fingers wouldn’t have cooperated.

With the rope sliced, he started the engine, praying that it wouldn’t stall. It started first time. Hollie pointed the boat away from the wave and hit the gas. He could hear the water crashing behind him like a waterfall. The boat lurched, the prow rising into the air and forcing Hollie onto his back, then it was crashing back down again, mini tidal waves rising above the deck either side of the boat as it landed, saturating Hollie’s clothes.

He wiped water from his eyes with his wet sleeve and grabbed the wheel. A glance over his shoulder, and he could see the gigantic wave foaming into the lake, the domino effect of the force causing another series of waves to lunge his way, while the tsunami kept coming.

There was no time to think about it. An image flashed into his head of the damage this must’ve caused between here and the ocean, and he shut it down. He had to focus. Hollie sensed the wave growing behind him and, knowing there was no time to outrun it, killed the engine, hoping to ride it out like a surfer. He clung to the wheel his knuckles white.

The wave seemed to dip beneath the boat’s stern and then raise its head like a serpent playing with its prey, knowing it was only a matter of time before it won. The boat was in the air, riding the crest of the wave. Hollie held his breath. Time stood still, and then it crashed down into the water, the entire prow sinking beneath the surface. Still clinging to the wheel, Hollie twisted his body around and dragged himself onto his knees on the flooded deck. He waited for the boat to right itself, water pouring over the windshield. Much more and the boat would go under. He couldn’t think about that. The seconds dragged by as the wave continued surging forward, sucking the boat along with it. It was heading toward the other side of the lake. From there, if it kept going, it would take out the residential areas closest to the water, the properties, the schools, the entire community.

Hollie started the engine, the motor squealing beneath him, then he turned the wheel. He was facing the north bank; if he could make it across the lake, he could warn people to get away, get to higher ground until this whole thing—tsunami or whatever it was—subsided.

But the roaring sound coming from the eastern side of the lake filled him with terror. Hollie looked around as another gigantic wave, taller than the first, loomed overhead, blotting out everything but the body of water that again reminded him of a serpent poised ready to strike. He had no time to react. The wave, reaching its highest point above him, suddenly dropped, the full force of the foamy water hitting Hollie’s boat.

Instinctively, he let go of the wheel and crouched on the deck, arms covering his head. It was a futile move. He felt the boat splinter beneath the weight of the water, and he was plunging down, debris from the boat, planks of timber, the locked cabinet containing the first aid kit, all sinking with him. Something hit Hollie’s head, sending him spinning backward. Arms and legs flailing against the current sucking him deeper and deeper, he ignored the sharp pain in his left thigh, the throbbing in his skull. He had to reach the surface. Had to breathe.

His eyes were stinging. He could see nothing but the remains of the boat hurtling around him as the water dragged it down. Hollie crossed his arms in front of his face as the motor spun toward him, kicking out with his feet to push himself backward, the motor skimming past his chest. His lungs were on fire. He looked up. He needed to reach the surface, but all he could see was water. Debris. Bits of his boat spiraling around him. He tried to splash, his legs and arms numb, and stared up at the surface which was still so far away…

🔴 Read Chapter 2 - John's New Place

🔴 Read Chapter 2 - John's New Place

Hollie parked his car on the driveway of a large, brick-built house, with wide bay windows and a red tiled roof. He peered through the windshield at the frost clinging to the tiles and the low shrubs lining the drive that sparkled in the morning sunshine. Now that he was here, he realized that it was an image of the house sitting in a snowy garden than had sold it to him, even more than the fact that it was once owned by a famous natural historian. The realtor hadn’t even needed to hard-sell it. Vermilion was a quaint, cozy town bordering Lake Erie. Peaceful. He’d already moored his boat here weeks ago. This was going to be his life going forward: every waking moment of his spare time outside of work spent relaxing in a neighborhood where he wasn’t constantly listening for police sirens.

“Don’t forget to send me pictures once you’re settled. Hollie?” He’d almost forgotten that his PA was still on the phone. “I want to see these spectacular views from your couch that you’ve been raving about for the past few months.”

Hollie smiled at the house, his shoulders already loosening even though he’d be spending the rest of the day helping the movers unload his belongings. “Will do,” he said.

“By the way, I’ve sent over the information for the new project,” Ann, his PA said, her efficient tone back. “Should be in your inbox now.”

Hollie was a civil engineer, specializing in city areas that were difficult to develop, where the land was unstable, saturated, or prone to movement. Fate had written in his stars that this would be his career path, so it was not a choice he’d ever questioned or regretted. Even as a child, he would spend hours figuring out how to build the tallest, narrowest towers with his Lego bricks. His bridges were always longer than those built by his friends. His fortresses were stronger. His mom always said that when she put his dinner in front of him, he’d try to build something with it first.

This passion for his line of work was what had prompted him to buy a property in an area that had history, his only real stipulation that it should be close to water and transport links. The first time he drove through Vermilion—he was working on a project nearby at the time—and saw the properties with their naval themes, he felt like he’d come home. He’d done some research. He discovered that Crystal Beach Park was built by a guy named George Blanchat in the early 1900s and named accordingly because his wife thought the sandy beach was like crystals. He read about the beach houses built on the lagoons, the famous ballroom and yacht club, and the history of McGarvey’s restaurant. It was a prime real estate area, and the house was probably a stretch even for Hollie’s decent salary, but somehow, he knew this was where he was meant to be, the instant he saw the ‘FOR SALE’ sign outside the house.

He was lured here, he told Ann, unsure how else to explain it.

“Thanks, Ann,” he said now. “The movers are here, gotta go.”

He ended the call and climbed out of the car. He hated lying to her, but she was one of those people who always seemed like they were starved of company, and if he let himself get drawn into a conversation about his new home, he’d still be talking while the men shifted furniture around him.

Turning his back to the house, he studied the views. The house was built on the street overlooking Linwood Park and beyond that the lake, and even if he could only imagine the lake shimmering in the distance, he’d still have been besotted with the view. The nautical-styled houses and quaint shops. The tree-lined avenues. The whole world moved at a different pace here.

He was still breathing in this new, clean air when the moving van pulled up onto the drive. For the next couple of hours, the two men and Hollie shifted furniture into the house, maneuvering the dog-leg staircase, and putting beds back together. He wasn’t a materialistic person, his love of architecture not extending to the stuff contained inside the buildings. What Hollie did possess though, had been bought with durability and comfort in mind. The squashy sofas. The solid pine closets. The artwork bought, not as an investment, but because he saw something in them that provoked an emotion deep within.

After the movers had gone, and Hollie was alone in his new house, he spent some time rearranging the furniture to make it look like home, then, satisfied, took some photos on his cellphone to fire through to Ann. He sat in the armchair and peered out of the window. It was a strange feeling, like having one foot in two different worlds. He was sitting in his armchair, and this was his coffee table in the middle of the room with his book The Lost Works of Isambard Kingdom Brunel on top, but he’d only taken the first step of this new adventure and couldn’t even begin to imagine where it would lead him.

As the sun drifted slowly toward the horizon, Hollie found a pizza delivery leaflet that the realtor had left on the kitchen counter with a hefty amount of junk mail intended for the previous owners. He ordered a pepperoni pizza with extra cheese and, when it arrived, sat at the breakfast bar in the kitchen and toasted himself and his new home with an ice-cold beer.

While he ate, Hollie read through the information that Ann had emailed across, studying diagrams, referring to the brief, checking and double-checking the land reports they’d been given. It was quiet—he’d barely counted half a dozen cars passing by his house, so he found a podcast on YouTube presented by his favorite comedian turned activist and campaigner, Jones Conrad, and switched it on just for some background noise. Besides, the guy talked more sense than most politicians and rather than losing fans with this change of direction, his followers had multiplied, drawn, Hollie supposed, by the comedy he still managed to inject into his podcasts.

Today’s conversation was about climate change.

Hollie wasn’t paying attention. He heard Conrad introduce a government climatologist called Paul Weathers—no pun intended—smiled to himself and turned the volume down. Climate change had been a part of life since before Hollie was born. It wasn’t that he was desensitized to it, but until the world’s leaders took it seriously and became proactive rather than reactive in their efforts to reverse the hole in the ozone layer, there seemed little anyone else could do other than continue to employ the little changes that would collectively make a difference. There were solar panels fitted to the back of this house. When working away from home, Hollie arrived by public transport and then walked around the city, and he recycled everything that he possibly could.

Immersed in the land registry documents he’d retrieved from his briefcase, checking that the initial planning application works had covered every eventuality, he didn’t glance at the laptop again until he heard the climatologist mention an event he called the Great Wash Out.

“Not to be confused with the Great Wipe Out,” Conrad said.

Paul Weathers gave a half-smile. “Wipe Out would indicate a lack of energy,” he said, his tone deadpan, “or another pandemic. We’ve learned to live with these problems.”

“So have the pharmaceutical companies.” The comedian grinned at the camera.

Hollie shook his head and turned his attention back to the thick pile of documents in front of him. He couldn’t concentrate though. This was the first day in his new home, and it felt wrong to be working when he should be outside exploring his new surroundings.

He went to the refrigerator and took another beer. It felt good. The last time Hollie had felt this excited was when he got his last promotion; it had been the result of several years’ hard slogging, and even though he knew he deserved it, he didn’t allow the buzz to take hold until he was physically holding the formal letter in his hand. It was the same with the house. The paperwork had been signed and completed weeks ago, but he’d kept his excitement on hold until today. He wasn’t going to get much sleep tonight.

The podcast was still going strong. The climatologist was talking about oceanic tectonic plates and how they were shifting with the effects of global warming.

Hollie swallowed a mouthful of beer and wiped his lips with the back of his hand. Sure, there’d been some coastal flooding around the States in recent years, but nothing to cause mass panic. He tried to recall the last tsunami he’d seen on the news reports, somewhere in Indonesia the previous fall. October, November maybe. He felt bad for the communities affected by these natural disasters, but again, it was out of his hands, and no one would ever understand the true horror of these events until it happened to them personally.

He peered out the window at the trees in his backyard. He’d never owned trees before, not that anyone could ‘own’ a tree in that sense, but until now he’d always lived in apartments. The higher above ground the better. Maybe he would even learn to grow his own vegetables—Ann would be impressed.

He heard the words Wash Out again and turned back to the podcast, leaning against the kitchen counter. Another expert had joined the conversation, a survivalist, who was obviously supplying basic survival guidelines for the listeners. “… make their way to higher ground.”

“What if that’s not an option?” Conrad’s expression was serious. “What about the folks who are a couple hundred miles from the nearest mountain? Should they get a boat? What do you suggest?”

“This is all hypothetical, remember,” the survivalist said. “Paul suggested that there’s been increased movement in the tectonic plates, but we’d have fair warning of any major disaster, right, Paul?”

“What do you think this is?” Paul Weathers had a habit of twisting his head to one side as if he had neck pain, Hollie noticed. Watching him, even from a distance across the kitchen, Hollie couldn’t help twisting his own head.

“No,” the survivalist continued, “I mean an official warning. The government has its own scientists, its own climatologists. You’re employed by the government yourself. So, when you know the tectonic plates beneath the ocean are about to cause a tsunami or, as you like to put it, a Great Wash Out—”

“I don’t like to put it that way,” Paul Weathers said. “That would imply that this is just some banter amongst friends.”

“Okay, so when the government knows the tsunami is coming, they’ll give the country a formal warning. They’ll tell us to get the hell up to those mountains and ride it out, right?”

When the climatologist spoke, his expression was unfathomable, his tone bland. “Get the hell up to those mountains and ride it out.”

Conrad laughed. “Hey, I’m supposed to be the comedian here.” Turning to the camera, he said, “That’s it, folks. Tune in next Friday to the next episode of the Great Wash Out. See you there.”

Smiling to himself, Hollie switched off his laptop, stacked the documents neatly on the counter, and went out to explore his new neighborhood.

🔴 Read Chapter 3 - John's New Place

🔴 Read Chapter 3 - John's New Place

John was in his kitchen drinking coffee and making pancakes for breakfast when there was a knock at his front door. It was another thing he had to get used to—not listening out for the buzzer to announce the arrival of guests. Smiling to himself, he turned off the heat and went to greet his first visitor.

“Hi, I’m Marsha Collins,” the young woman said. “I live just down the street.” She pointed to her left. She had a wide smile, the kind that got other folks smiling because it lit up her face reaching her eyes and ears and hairline. She was wearing sweatpants and a long-sleeved T-shirt with a smear down the front to which she seemed oblivious.

“Hello, Marsha Collins,” Hollie said, offering her his hand. “John Hollie. I’ve been Hollie since I was a kid, and it’s kinda stuck. Good to meet you, neighbor.”

Marsha wiped her hand on her sweatpants before shaking. “Sorry … kids. One wanted chocolate spread on his toast. One wanted peanut butter and banana. You get the picture.” She waved a hand to dismiss the subject.

“Wow. You’ve got two kids.”

She didn’t look old enough, Hollie thought. Take away the stained T-shirt, she looked remarkably fresh and unscathed by the whole motherhood thing, not that Hollie was an expert in these matters. Her blonde hair was thick and wavy, the kind of hair some girls he’d dated in the past would pay a fortune for. But maybe Marsha’s was all natural.

“Four. I know,” she quickly added, “I always get the same reaction. I’m one of those crazy women who had them all a year apart. I always wanted to be a mom, and it seemed the natural thing to do—have them close together so that they’d all grow up looking out for each other.” She grimaced. “That’s what I remind myself when the baby screams because she’s teething, and she wakes the boys up. You ever played with spaceships in the middle of the night? Don’t answer that.” She laughed out loud.

Hollie grinned. The laughter was infectious too. “I was a Lego kid.”

“Oh, we have Lego too. Maybe you should come over sometime and entertain the kids. Only joking. I wouldn’t inflict that on you.”

“I’d love to,” Hollie said before he could stop himself. “They might not like it though. I’m a civil engineer, which kinda makes me a bit controlling when it comes to building stuff.”

Marsha puffed up her cheeks. “Ooh, a civil engineer. You’ll get along with my husband, Jimmy. He loves taking things apart and building them back up again. He works in the boatyard, although sometimes I’m sure he wishes he worked further away.”

His neighbor was like Ann, a talker. Hollie had always been a thinker; even in school he was the quiet kid who only ever raised his hand in class when he was certain he had the correct answer, and by then he was usually too late. He didn’t really fit in with any of the cliques. He wasn’t a jock, which excluded him from the popular group. He wasn’t into science, so the geeky kids never considered inviting him into their group either. Not that it ever bothered him—when he made friends, he was loyal to them, and vice versa. Maybe it was this unobtrusiveness that attracted women who could fill the gaps.

“I’m sorry,” he said. “I haven’t even invited you in.” He stepped back and opened the door wide, giving his neighbor space to come inside.

“Oh, no, it’s fine.” Marsha waved a hand in the air again, and Hollie noticed the perfect pink fingernails. “I’ve left Jimmy in control of breakfast, and it can get a bit messy, you know. He’s all right when he’s chasing them around the garden and burning off some energy, but he draws the line at getting peanut butter in his hair and oatmeal kisses.” She giggled again. Hollie guessed that having four kids in four years would make you look for the funny side in everything.

“Another time then,” he said.

“For sure. I love looking around people’s homes. I bet you’ve got a Starbucks couch placed in exactly the right place for you to admire the view, and some decent artwork hanging over the fireplace.” She raised her eyebrows. “Am I right?”

“A Starbucks couch?”

“You know, one of those big, squashy ones that you sink into. I can never get out of them unless someone gives me a hand.”

“Surprisingly accurate then,” Hollie admitted.

“I knew it! The couple who lived here before kept it quite traditional, you know. Floral furniture and matching curtains. Tasseled cushions. A gilt-edged mirror over the fireplace.”

Hollie smiled. “And there I was thinking that you were psychic or something.”

Marsha shook her head. “I just like people watching. Speaking of which, the reason I came here was to tell you about the barbecue tomorrow. Jimmy was going to come and speak to you, but I’ve been up half the night, and I just wanted a breather, so I beat him to it.”

“Barbecue?” Hollie prompted.

“The block association. We have a barbecue every couple of months, and always on a Sunday so that everyone can come. It’s a great way for you to meet the neighbors without having to go knocking on folks’ doors for a cup of sugar.” She laughed again. “We’re a nice bunch of people, and we don’t bite.”

Hollie smiled. “Sounds great. What do I bring?”

“A bottle of wine if that’s what you drink. We all chip in for the food, but I’m sure Paddy will find you and fill you in on how it works. Paddy’s the guy who set up the block association after his wife died. I think he needed something to focus on, and everyone was so cut up when Marie died, that we all agreed without even thinking about it. It’s been going strong ever since.”

“Great. I’ll speak to Paddy tomorrow then.”

“I’ll introduce you to Jimmy,” Marsha said. “A word of warning though. Susie from number seventeen will eat you for breakfast if you’re not careful.”

“O-kay. Should I be worried?”

“Depends on whether you like your women glamorous or not.” Marsha went to walk away and then stopped when she reached the edge of the porch. “Almost forgot. It’s in the park. You’ll smell the steak before you arrive.”

Hollie found Paddy overseeing the barbecue when he arrived. He was a giant of a man, broad-shouldered, with ruddy, weathered cheeks and a bushy, ginger beard. His handshake was strong.

“John Hollie. I just moved to the area.”

“Good to meet you. Patrick McConnell, but most folks know me as Paddy. I swear if someone called me Patrick now, I’d be looking around to find the guy.” He smiled and offered Hollie a plastic cup. “Drink what you like, eat what you like, all we ask is that you pick up your trash.”

“Goes without saying,” Hollie said.

The guy had a gentle aura—a gentle giant some might say—the kind who was friends with everyone, until someone did him dirty.

“Make yourself at home. I know I’m biased,” Paddy said, “I’ve lived here all my life, but this is a great community. We’ll welcome you with open arms. Mi casa es su casa, and I genuinely mean that. Any time you got a problem, you come find me, and if I can help, I will.”

Hollie believed him. He liked to think that he was good at reading people, and everything about this guy said that he was genuine.

Paddy clapped him on the shoulder with his large, heavy hand. “Go mingle. Enjoy yourself. Eat. No one leaves Paddy’s barbecue hungry.”

Hollie glanced around. The only person he knew was Marsha, and he couldn’t spot her anywhere. She might be running late with the kids, he guessed. The park was pretty, the kind of place that conjured up images of bandstands and carousels with painted horses and women wearing wide skirts, shielding their faces from the sun with frilled parasols. He saw a group of people around his own age—three couples—the men drinking beer from plastic cups, their partners sipping white wine. He was about to go and introduce himself when a woman appeared in front of him.

“Hi, I’m Susie.” She didn’t wait for him to offer his hand in greeting but reached up and kissed both cheeks. Hollie inexplicably felt heat flooding his face; he wasn’t easily embarrassed, but she’d caught him off-guard. “I saw the movers shifting your furniture. I was going to knock to see how you were settling in, but I didn’t want you to think that I’m forward or anything.”

“Nice to meet you, Susie. I’m settling in just fine.”

“I see you brought red wine,” Susie said, eyeing up the bottle in his hand. “I’m a white wine kinda gal.” She raised her cup to show him. “What do you think of us so far?”

He assumed by ‘us’ she meant Vermilion in general. “Honestly, I love it here,” he said. “Coming from the city, the peace is going to take some getting used to, but it’s the reason I bought the property. Somewhere to unwind close to the lake.”

“City boy, huh?”

If Hollie had met Susie on neutral territory, he’d have pegged her as a city lass herself. She was wearing tight jeans and a gold shirt unbuttoned to reveal her collarbones and the edge of a black lacy bra. He guessed she was in her early forties even though she looked younger; something about her body language radiated experience. Susie knew how to dress, and she knew what suited her; she was done following trends and trying to be twenty-one again. He liked that in her.

Hollie explained that he was a civil engineer working on city developments. “I’m planning on dividing my time between home and the city when I need to be on site.”

Susie shook her head. “I don’t know how people do that, working away from home. I like my creature comforts too much. Stick me in a hotel room, even an expensive one, and I guarantee I’ll get no sleep.”

The innuendo wasn’t lost on Hollie. He grinned at her. “I sleep like a baby. I guess you just get used to it.”

“Have you had a chance to explore yet?” Susie asked.

“Not yet. Got any suggestions?”

“You must visit the islands, and there are a few great restaurants that you should try if you don’t fancy cooking one night.”

He wondered if she was hinting at maybe going with him one evening. After Marsha’s comment, he’d half-expected to have to fend Susie off while she clawed at his shirt, but if he was honest, he liked her. “Sounds like a plan,” he said. “Let me know when you’re free.”

Susie’s eyes widened. “I will, Mr. Hollie. You just let me know the kind of food you like, and I can show you where to get it.” Her cheeks grew rosy, and she sipped her wine as if to cool them. Hollie wondered if her glamorous image had given her a reputation as a man-eater that she enjoyed perpetuating; he was quite intrigued to find out.

Marsha and Jimmy came over then with their children. The little girl was in a stroller—she wore a pink dress and sparkly trainers and had the biggest eyes Hollie had ever seen. She was the image of her mom. The three boys ran around the small group in circles.

“Jimmy Collins.” Marsha’s husband shook Hollie’s hand, oblivious to the whoops and laughter of his children. “I’m going to count to three,” he said firmly, “and then you’re all going to stop.”

Hollie couldn’t help laughing when he realized Jimmy was talking to the boys. Susie snickered behind her wine glass.

“Sorry. It’s impossible to have an uninterrupted conversation when you’ve got kids.”

“I manage just fine,” Marsha said.

“That’s because you’ve learned to ignore them.”

“It’s the only way.” Susie winked at Marsha. “Wait till they’re teenagers.”

“Oh God.” Jimmy groaned. “You mean it gets worse?”

Hollie spent the afternoon getting to know Jimmy and Marsha a little better. Susie mingled with her friends, but several times Hollie glanced at her and caught her eye, and she flashed him a dazzling smile. Paddy came over to make sure that he was doing okay, and to explain how the block association worked. Hollie immediately signed up for it—this was home now. By the end of the afternoon, when Marsha and Jimmy had taken their exhausted children home to get them bathed and into bed, and the barbecue had stopped smoking, Hollie felt, for the first time in his life, like he belonged.

House of Light Series: Discover the journey of one stranded family 🏠💡⛈️

House of Light Series: Discover the journey of one stranded family 🏠💡⛈️

"My wife, Onnie, and I are on the run for weeks now. The city we once called home descended into chaos after the fall. We've had no choice but to flee with our son, Sirus, and hope to find refuge elsewhere.As we journey through abandoned towns and desolate landscapes, our hope begins to dwindle. But then, a miracle. We stumble upon a beautiful farm house sitting in the middle of a field, seemingly untouched by the chaos of the outside world. That's when we noticed the lights. It's strange, to say the least.We're soaked to the bone and desperate for shelter, so we take our chances and rush inside, grateful for shelter from the sudden storm that seems to have come out of nowhere.As we explore the house, the mystery surrounding the lights only grows. They seem to be on all the time, even though there's no power source we can see. But we're too tired to think about it too much, and we're just grateful for a roof over our heads. The only problem is, the lights are a beacon and they never turn off..."

🔴 Read Chapter 1 - See the Light

🔴 Read Chapter 1 - See the Light

“Monty, I’m tired. I’m tired. I can’t take another step.” The words tumbled out of Onnie Newton’s dry mouth in a rush as she gazed down at her tennis shoes. The tongues lolled out in crumpled angles and the laces were gone, along with a few of the silver rivets. The shoes were once white but were now a shade of smudged dove grey. All of this she barely viewed from the edge of her swelling stomach. She knew there were holes along the edges of her insole, but the frayed ends were behind the toes, and she had not seen them for at least a month from a standing position. She wore a wispy cotton floral navy dress they’d found somewhere in the last town. Pants were no longer efficient; the bands rubbed too much along the line of her belly, creating itchy wide red marks by the end of their daily travels. They walked all day, all week, all month and into a few years since the catastrophe, never staying too long in one place or the next. But they would have to stay somewhere soon…at least for a little while, until the baby came, and that wasn’t far off. She wasn’t sure of the exact date the big event would take place but by the looks of things, in the next few months.

“It’s all right, baby. We need to take a break. Thank you for not pushing yourself this time.” Monty ran a hand over his nearly bald head. Sweat glistened against the dark curly strands. This was his figuring it out motion, a motion Onnie became used to long ago. She watched him scan the horizon, where old houses sprouted like dry wheat. Some held a promise. But promises were often a ploy to get you murdered, a hard lesson they’d so far evaded.

“It’s midday and the sun is blinding,” Monty said. Then he glanced back and said, “Sirus, catch up, son. You know we don’t like you straggling that far back. It’s not safe.”

“Dad…you’re standing still. We’re not in a hurry. No one’s around. And it’s hot. Can we at least find shade?”

“Don’t. Yell.” Monty’s voice barely contained his ire.

Onnie took a step toward her husband. Her hand reached for his. “He’s just a boy, Monty. He’s doing the best he can for a five-year-old.”

His fingers weaved between hers on contact. He took in a breath and let it out, nodding as he closed his eyes for a moment.

That’s when she kept hers open and scanned the horizon for any unusual movement. When Monty was off, she was on. They no longer needed to say the words, with a habit established long ago.

When Sirus met up with them he leaned his head into her side, his slim arm coming up around her belly.

Both her men at her side, she watched the amber grass waving in the dry wind. With the palm of her right hand, she shielded Sirus’ head from the sun’s harsh rays and beads of sweat formed almost immediately. She said absently, “You need your hat on your head.”

Then, without a response, a moment later she said, “Monty, there’s a house over there in that field by an old barn. There might be a chicken or two strayin’.”

He lifted his head and pulled away, swiping a spray of sweat to the dirt road.

She pointed her arm in the direction of the two-story home engulfed in an overgrown corn field.

His eyes lingered there a moment, then he looked around again at the other options and without a word he adjusted the pack on his back and picked her bag up from the dusty road. “Good a choice as any, I suppose. Come on, Sirus. Help your mom across the field.”

“Is it going to rain?” Sirus said, as he took hold of her sweaty hand.

Onnie looked again at the sky. “I sure wish it would. Even warm rain would cool things off a bit.”

“There’s a cloud over there.” Sirus pointed. “Right over that house we’re headed for.”

“I see that. I didn’t notice it before,” Onnie said, as she began to cross the ditch leading to the field. Monty held out his hand and eased her balance while she traversed the ravine.

“There’s a deer trail through the field but watch your hands along those sharp, dry stalks. They’ll cut you up if you’re not careful.”

She’d heard this same warning nearly every single time they crossed a field and apparently so had her son, because when his eyes met hers, they rolled slightly. Who taught him to do that, she wondered? They rarely met other children his age and yet this reflex still existed. She couldn’t help but smile.

“Take it easy here, Onnie. The ground’s uneven,” Monty said, and when she looked up, she saw that he’d stopped in his tracks and then, so did she, halting her son’s next step.

“What is it?” Sirus’ words came in a whisper, sensing something was wrong.

But she didn’t answer as she felt her son’s eyes first linger on her face for an answer, and then he looked to his father, farther down the trail.

She barely moved but her eyes darted from one direction to the other. Should she run, dragging her son with her? And if so, which direction? All she needed was a signal. A signal from her husband. But Monty stood silently twenty feet ahead with his back to her as he stared at something on the ground.

With a hush that dragged on, a dry breeze seethed and clattered thirsty cornstalks together like rushing bees in a funnel. The sound was so eerie that every whisp of hair along her arms stood in silent salute. Her grip on her son’s hand tightened and yet Monty still gave no signal. Ready to bolt, she lifted a handful of her thin cotton dress as a torrent of rain dumped from the sky. And in the sudden darkness, that’s when she noticed the lights brightening the windows of the house beyond the field.

Onnie’s mouth hung open. Wet drops pelted her head, clung to her eyelashes, and yet she could not tear her eyes away from the steady golden beams shining through the squares. There were no flickers from a fire flame. There were only steady lights, firm in their existence. An existence that neither she nor Monty had seen in years.

“What does it mean?” Her voice was full of surprise.

She found Monty watching her, having lost interest in whatever transfixed him before. His face was dark and vacant, heedless of the rain drenching him.

“Come on.” Monty’s voice raised over the din, then he nodded in the direction of the house.

Onnie, shook her head. “No,” she began to say but Monty came to her in a rush and grabbed her arm, urging her and Sirus down the path.

“We need to get out of the rain.”

“But Monty, we haven’t…” she began and as he tugged her farther, her steps fell onto something firm—not the earth, but something hard and rigid. She looked down but Monty kept her moving and in another two steps she again felt the familiar sponge of weeds beneath her feet and then a sharp sting along her arm where a razor-edged stalk caught her flesh.

“Mom…what’s that light?” Sirus said.

But there was no time to explain as Monty hauled them both up and onto the steps of a wooden porch as if there was an enemy rushing behind them. Only there was no refuge from the rain there. Stinging darts came in sideways and pelted them from every corner, as if the sudden storm was trying to blind them and shove them through the folds of a knot.

That’s when Monty’s hand landed on the door’s knob. That’s when terror struck through her like a bolt of lightning. Don’t! Don’t open that door!

On the other side, Monty struggled to close the gap against the storm. Leaning all his weight, he dropped her bag to the tiled ground and shoved hard against the load as the entrance threatened to defy his effort.

In an instant, Onnie pushed her son away as she leaned her weight too against the burden. And then she watched as Sirus added his own effort, with both palms pressed against the wood between his parents. The lock finally hit purchase, and everything stopped.

With the storm finally trapped on the other side, Onnie shut her eyes, shut her mind. Because what they’d just done was unthinkable.

“Hello?” Sirus said.

Onnie’s eyes flashed open. “What are you doing? There might be someone here.”

“That’s what I’m trying to find out.”

Monty pulled away and then pulled Onnie by outstretched arms until she stood straight and steady.

“What happened out there, Dad?”

Monty shook his head. “I can’t say, son.”

But Onnie wasn’t sure what exactly that meant and remembered the hard thing she’d trodden over to get to the house. “What was…”

“Hello? Is there anyone here?” Monty took another step into the foyer on the puddled tile floor.

“It’s cold in here. What are those lights from?” Sirus said, pointing and following his father’s steps.

“No. Don’t.” Onnie reached for her son and pulled him back until his head touched her belly. “It is cold. Is that air conditioning?”

Monty’s hand reached out to still them in place. “I’m going to look around. You stay here.”

Shaking her head, “No. That’s not a good idea. Don’t leave us here.” Panic rose in her voice like a hawk riding the wind.

“It’s just a house, and there’s got to be a generator keeping those lights on.”

“I don’t hear a generator, Monty. There’s no sound. I mean, like no sound. Not an engine. No one’s answering. And the lights? This isn’t right…”

Then he did something she never expected. He turned to her, and he smiled. “Pretty cool though, huh?”

In a whisper, she asked, “Monty…what’s keeping the lights on?”

He looked up at the foyer’s chandelier. “I imagine,” he said as he noticed a lamp shining brightly on a table below a gilded mirror, “it’s some sort of generator. We just haven’t found the source yet.”

“Are we going to stay here, Mom?” Sirus whined.

“No baby. We are definitely not staying here,” she murmured back as Monty attempted to turn off the lamp’s switch.

With a click, he glanced under the shade, the light blinding him.

“Maybe you have to do it twice. I remember sometimes, we had to turn the knob more than once.” She held her fingers in the air as her thumb enclosed an imaginary handle as she turned her wrist.

“I know how to turn on a light, Onnie.”

“Can I try?” Sirus asked.

Onnie pulled him back by the end of his shirt. “No. You will not be touching that light. Sit right here by the door with me.”

By the time Onnie asked, “Are we sure there’s no one in the house?” Monty had rotated through twelve more clicks and still the light refused to even dim.

He stopped and looked at her. “I’m sure they would have introduced themselves by now.” He sat the lamp back down. “Well, I don’t know.”

“Maybe unplug it.”

Monty nodded. “Should have thought of that. Wait, there’s no cord attached to this thing. Why isn’t there a cord?” He looked at his wife as if she might have the answer. “Babe, just turn off the switch to that one,” he said, pointing to the overhead sconce above their heads.

She turned to the wall, ran her hands behind the entrance’s wispy curtain and pulled the fabric away from the wall, revealing no control switch for the light. “I would if I could find the switch plate. Monty, this is just too weird. I don’t like this place. The storm sounds like it’s over. I think we should leave.”

Monty looked at his family and nodded. “Okay. I guess you’re right. I liked the idea of sleeping indoors tonight. Sirus, pick up your mom’s bag. Maybe we can stay in the barn. It’s probably dry there, at least for the night.”

“I’d rather find another farmhouse,” she said as she tried the door handle. But as soon as she twisted the knob, the abated storm revived once again.

Monty slapped his hands against the door above her head, sealing it to the jamb. “No way. I’m not taking you out in that.”

“I couldn’t hear it a second ago.”

“Probably good insulation. This place doesn’t look old. At least we can stay one night, Onnie. If there was someone here, they would have torn down those steps by now.”

“These lights didn’t turn on by themselves, Monty. Someone lives here and they’re going to be pretty upset when they find us in their house. Maybe they’re out scavenging.”

“You think maybe they’re away? And they just left their lights on in midday, when no one’s seen electric lights without a generator in over a decade?” Monty asked.

“I don’t know what’s going on, babe.”

“What I know is that we’re not going out there until that storm passes. Not in your condition. Let’s look at the rest of the house and make sure it’s empty and then we’ll camp out near the door if that makes you more comfortable.”